Bisection in Two Dimensions

We describe basic idea of the newest vertex and the longest edge bisection

algorithm for two-dimensional triangular grids. In short, a bisection refinement will divide one triangle into two children triangles by connecting one vertex to the middle point of its opposite edge. Another class of mesh refinement method, known as regular refinement, which divide one triangle into 4 similar small triangles, is implemented in uniformrefine.m.

There are two main issues in designing a good bisection method.

- (B1) Shape regularity.

- (B2) Conformity.

Newest vertex bisection

If one keeps cutting one edge, the smallest angle will decrease and approach to zero. To keep the shape regularity, we can switch the edge to be cutted.

Newest vertex bisection

Newest vertex bisection is to assign the refinement edge as the edge opposite to the newest vertex added in the bisection. To begin with, for an initial triangulation $\mathcal T_0$, we can label the longest edge of each triangle as the refinement edge. Once a initial labeling is assigned to $\mathcal T_0$, the refinement edges of all descendants of triangles in $\mathcal T_0$ is determined by the combinatorial structure of the triangulation.

It can be shown that all the descendants of a triangle in $\mathcal T_0$ fall into four similarity classes and hence (B1) holds. See the following figure for an illustration

Refinement edge

How to represent a labeled triangulation? Recall that our representation

of a triangle: elem(t,[1 2 3]) are global indices of three vertices of

the triangle t. The only requirement on the ordering is that the

orientation is counter-clockwise. A cyclical permutation of three indices

still represents the same triangle. We make use of this room and use the rule:

The refinement edge of

tiselem(t,[2 3]).

In other wordes, for the newest vertex bisection, elem(t,1) will be always the newest vertex of the triangle t.

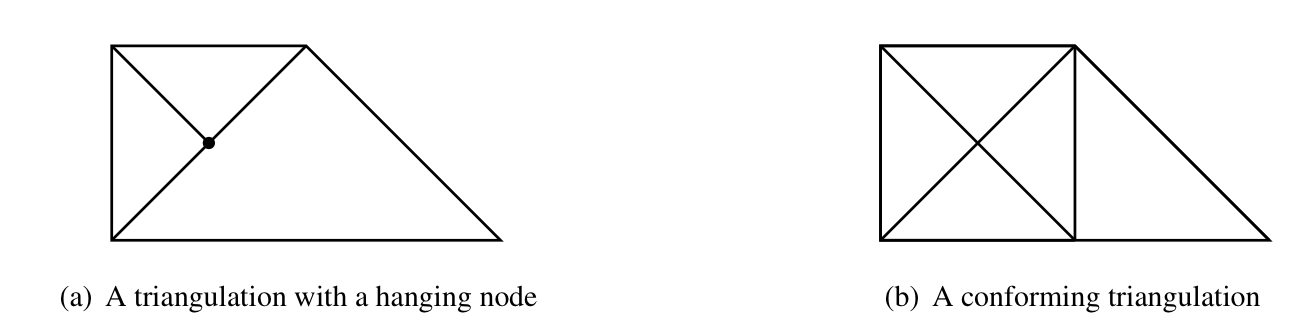

Completion

Bisect some traingles in a triangulation could result in hanging nodes. Neighboring triangles should be bisected (again following the newest vertex rule) to eliminate hangning nodes. This procedure is called completion.

We now describe an efficient completion algorithm for 2-D triangulations. A key observation is that if we cut all edges of the current triangulation (by the newest vertex bisection rule), it results in a conforming triangulation. Therefore instead of operating on triangles, we cut enough edges to ensure the conformity.

Let us denote the refinement edge of t by cutEdge(t). We define the

refinement neighbor of t, denoted by refineNeighbor(t), as the

neighbor sharing the refinement edge of t. When cutEdge(t) is on the

boundary, we define refineNeighbor(t) = t. Note that cutEdge(t) may

not be the refinement edge of refineNeighbor(t). To ensure the

conformity, it suffices to satisfy the rule

If

cutEdge(t)is marked for bisection, so iscutEdge(refineNeighbor(t)).

See bisect.m adding new nodes section.

%% Add new nodes

isCutEdge = false(NE,1);

while sum(markedElem)>0

isCutEdge(elem2edge(markedElem,1)) = true;

refineNeighbor = neighbor(markedElem,1);

markedElem = refineNeighbor(~isCutEdge(elem2edge(refineNeighbor,1)));

end

edge2newNode = zeros(NE,1,'uint32');

edge2newNode(isCutEdge) = N+1:N+sum(isCutEdge);

node(edge2newNode(isCutEdge),:) = (node(edge(isCutEdge,1),:) + ...

node(edge(isCutEdge,2),:))/2;

Bisections of marked triangles

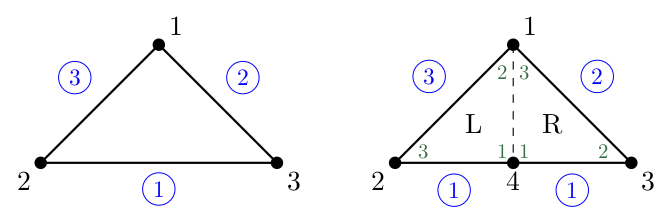

We only need to bisect the triangle whose refinement edge is bisected.

The local numbering is shown in the following figure. We only need to bisect the triangle whose refinement edge is bisected. The local numbering is shown in the following figure. Note that we repeat the bisection only twice. No loop over all triangles. We also need to

update the boundary condition i.e. bdFlag.

%% Refine marked elements

Nb = 0; tree = zeros(3*NT,3,'uint32');

for k = 1:2

t = find(edge2newNode(elem2edge(:,1))>0);

newNT = length(t);

if (newNT == 0), break; end

L = t; R = NT+1:NT+newNT;

p1 = elem(t,1); p2 = elem(t,2); p3 = elem(t,3);

p4 = edge2newNode(elem2edge(t,1));

elem(L,:) = [p4, p1, p2];

elem(R,:) = [p4, p3, p1];

elem2edge(L,1) = elem2edge(t,3);

elem2edge(R,1) = elem2edge(t,2);

NT = NT + newNT; Nb = Nb + newNT;

end

Initial labeling

Although the completion procedure we proposed will terminate for

arbitrary initial labeling, for the sake of shape regularity, we assign

the longest edge as the refinement edge of each triangle in the initial

triangulation. The subroutine elem = label(node,elem) will permute the vertices such that elem(t,2:3) is the longest edge of t. Note that it is only need for the initial triangulation.

Longest Edge Bisection

It is interesting to note that if we call label before each call of

bisect, then bisect becomes the longest edge bisection since

everytime we switch the refinement edge to the longest edge.

The longest edge bisection will produce shape regular triangulations. Intuitively the longest edge bisection divides the largest angle, which in turn prevent forming small angles. Rosenberg and Stenger proved that by always bisecting the longest edge, the smallest angle possible is half of the smallest angle in the initial triangulation.

Comments